LEADER OF THE PACK

by Donna Fenn

One way for a small company to grow in a cutthroat market is to pick one of the countless competitive strategies available and ride it for everything it's worth. Another way is to pick them all.

Chris Zane's competitors don't like him much.

Though his business is still small ($1.2 million in 1995 sales), 30-year-old Zane is already the largest independent bicycle dealer in the New Haven, Conn., market. He's confident. ("Let Wal-Mart come--I'm ready," he boasts.) He's combative. ("I'll put you out of business," he's said to other dealers.) And, most important, he'll do almost anything to attract and keep customers. ("I'll give you lifetime service, guarantee you the lowest price, fix you a cappuccino.")

He'd better. Like similar retail businesses all over America, Zane's Cycles is under siege. Superstores and chains have taken over, leaving specialty bike retailers with only one out of every four sales; in Zane's market, three independent bike shops went out of business last year alone. "The smaller guys are fading away because they won't get into the game and compete at a higher level," says Craig Seeger, a Trek sales representative serving Zane's.

Far from fading, however, Zane has gained market share--growing his business 25% a year by putting into practice every customer-winning tactic he can think up, adapt, or steal. He has read the management tomes, sought out gurus, picked his suppliers' brains, conducted focus groups, and studied customer behavior in his own store and elsewhere. He aims, he says, not to sell to customers but to own them.

To be sure, Zane's kitchen-sink-included competitive strategy can appear scattershot. His story contains half a dozen fashionable management ideas: continual learning, the lifetime value of a customer, guerrilla marketing, bootstrapping, community-relations marketing, cost-controlled customer service. And his success begs a handful of questions: How did Zane's Cycles, an ordinary business in an extraordinarily competitive industry, create a service standard that has become his market's price of entry? How has it become the region's most visible bike shop? How has it turned intimacy and ingenuity into competitive advantages that not even the hyper-professionalized chains can match?

But what Zane's story is really all about, what binds those ideas and questions together, is a mentality that Zane insists no business--even the smallest--can do without. Call it nonstop, no-limits, no-scheme-is-too-small competitiveness.

Even better, Chris Zane would tell you, call it fun.

Zane launched his first serious assault on his competitors 10 years ago, by offering one-year service guarantees (covering parts and labor on all routine service) when everyone else was promising 30 days. "It took them two years to realize we were taking market share away from them, and then when they started offering a year, we offered two," recalls Zane. In 1986 he learned at a Manhattan trade show that some dealers were offering five-year service guarantees. "I figured that for most people, five years is the life of the bike," says Zane. "If they've had it for longer, they're probably not riding it that much, so your liability on service would not be that great." Why not, he mulled, offer lifetime free service?

Zane launched his first serious assault on his competitors 10 years ago, by offering one-year service guarantees (covering parts and labor on all routine service) when everyone else was promising 30 days. "It took them two years to realize we were taking market share away from them, and then when they started offering a year, we offered two," recalls Zane. In 1986 he learned at a Manhattan trade show that some dealers were offering five-year service guarantees. "I figured that for most people, five years is the life of the bike," says Zane. "If they've had it for longer, they're probably not riding it that much, so your liability on service would not be that great." Why not, he mulled, offer lifetime free service?

"The core of my comfort is percentages. Everyone uses the free service the first year they have the bike, but I saw only 20% to 30% come back the second year. I figured my liability for lifetime free service would be minuscule." So in 1987 Zane raised the bar to the last notch, announcing free lifetime service on all bikes and making the offer retroactive. "We wanted to make our existing customers our apostles," he says.

His competitors balked. "Free service for as long as you own the bike is ludicrous," says John Budd, general manager of Action Sports. "But we've matched Zane tooth and nail." His shop now offers lifetime free service, as do most other bike retailers in Zane's market. Many feel they have no choice, and they're resentful that Zane has forced their hands. One dealer called him last year with a proposition: "I'll drop the lifetime service guarantee if you will." Zane just laughed. He had come to regard the guarantee as the foundation of his business and had extended it to everything he sold. "A guy once came in with a six-year-old pump that had worn out," recalls Zane. "I just gave him a new one."

Why? Because of Zane's bet on what that customer's lifetime of business would be worth to his store. "The guy had spent $60 on the best pump you can buy," he says. "So he's a premium purchaser, and here I have a chance to have him fall in love with us." Because Zane had a good relationship with the manufacturer, he knew he could send the broken pump back and get credit, no questions asked--so the cost of the return was zero. The potential payoff, however, was big enough that even if Zane had been forced to absorb the cost of the pump (about $30), it still would have made economic sense for him to take it back.

Consider this: "The guy has been in twice since then," says Zane. "He's probably spent $200 on accessories [a $100 net to Zane]." And when it's time for a new bike, Zane's betting that he'll get first shot at the sale. At an average cost of $400 for a bike, with a 35% margin, he stands to make another $140. And let's not forget the intangibles. A customer who is, well, thrifty enough to have a pump repaired is likely to be so impressed with getting something for nothing that he'll spread the word. "I'll bet he's told everyone about it," surmises Zane. "Everyone" probably being other serious and heavy-spending biking enthusiasts like the pump purchaser himself. In other words, Zane's ideal prospects.

So, the total invested: $30 (assuming Zane hadn't been able to get a manufacturer's refund). Total to the bottom line: $240, plus the profit from referral business. The result: a minimum 700% return on investment.

Chris Zane's continual business education had started long before he could imagine computing the lifetime value of a customer--and it always focused on service. "If you give good service, you'll stay in business," one of his first mentors told him. "If you don't, you won't."

"Thanks, Mom," said Chris to Patricia Zane.

That was when Chris Zane was a teenager, and his company-building career was already under way. It had started in a garage when he was 12 years old and fixing bikes for his middle-class East Haven neighbors. The mechanically gifted Zane learned that a kid who delivered what he promised and made his customers his first priority could make out pretty well. "If he told someone he would fix a bike, he would do it, even if something else came up," says Patricia Zane.

Friends told their parents, and parents told their friends, and Chris Sane was soon pulling in $300 to $400 a week. "I had a Connecticut state tax ID number when I was 12," he recalls. "My dad made me get it." When he turned 16, Zane thought it was "time to get a real job" and started knocking on bike shops' doors. He landed in a downtown Branford shop but was soon told by the owner that he had better start looking elsewhere--the shop was going out of business. Zane's wheels began to turn.

"I told my parents I wanted to buy the inventory and take over his lease," he recalls. Most parents would have dismissed the idea as a childish whim, but, says Zane's mother, "we knew if he was committed to something, he would follow through. He wasn't a quitter." And Patricia and John Zane were quick to recognize a negotiating opportunity. They agreed to let their son borrow $20,000 from his grandfather on three conditions: Chris would pay back the five-year loan with 15% interest; his mother would tend the shop in the morning, but Chris would come in every day after school and do his homework at night; and, most important, his parents and grandfather would hold all the stock until he completed college. "All through high school I told my parents I wasn't going to college," says Zane. "But they told me they wouldn't give me ownership until I had a degree." He agreed.

He racked up $56,000 in sales that first year and managed to increase revenues by 25% annually over the next two years, an accomplishment that gave him self-confidence--a bit too much, perhaps. When he turned 18, Zane began to think it was time he stopped doing gear adjustment and started sitting behind a desk, leaving the hands-on business of customer service to his two employees. It didn't last for long. "I started to hear from people that the store didn't have the same feel," says Zane. "Things would slide, and we saw that business was flat. Then I woke up and put all my eggs in the service basket. "The attitude changed from 'The customer is inconveniencing you and preventing you from doing your job' to 'The customer is your job,' " says Zane.

Over the next several years, he went out of his way to forge relationships with customers that would tie them to him for life. Guided by gut instinct and the ability to assimilate and apply every bit of information that might be useful to his business, Zane differentiated himself in the marketplace with a number of innovative tactics. The real kicker: like the lifetime free-service guarantee, Zane's service and marketing gambits often look expensive but usually cost him very little. Some examples:

- NO MORE NICKEL-AND-DIMING.

"We stopped charging for anything that cost less than $1," says Zane, who started that policy 10 years ago. A customer who wanted, say, a master link--an inexpensive part that holds the chain together on a child's bike--would be given one free. "The cost to me is virtually nothing," says Zane. "We're not going to chase the pennies--we're looking at the long-term effect of giving someone a master link. You should see the look on people's faces." The annual cost: less than $150.

"We stopped charging for anything that cost less than $1," says Zane, who started that policy 10 years ago. A customer who wanted, say, a master link--an inexpensive part that holds the chain together on a child's bike--would be given one free. "The cost to me is virtually nothing," says Zane. "We're not going to chase the pennies--we're looking at the long-term effect of giving someone a master link. You should see the look on people's faces." The annual cost: less than $150.

- COMMUNITY-SERVICE MARKETING I.

Zane's parents raised him with the expectation that he would give something back to the community, and he has. But he's also discovered that being a good citizen pays off. In 1989 he started the Zane Foundation, which now awards five $1,000 college scholarships to Branford High School seniors. He has financed the scholarships with revenues generated by 50 candy machines, scattered throughout the Branford area. All are labeled with Zane Foundation placards. "We're doing something our competitors aren't and that the category killers aren't. If people see that we're taking care of the community, they're more likely to come to us." After an initial investment of $2,500, Zane says, the program has paid for itself.

Zane's parents raised him with the expectation that he would give something back to the community, and he has. But he's also discovered that being a good citizen pays off. In 1989 he started the Zane Foundation, which now awards five $1,000 college scholarships to Branford High School seniors. He has financed the scholarships with revenues generated by 50 candy machines, scattered throughout the Branford area. All are labeled with Zane Foundation placards. "We're doing something our competitors aren't and that the category killers aren't. If people see that we're taking care of the community, they're more likely to come to us." After an initial investment of $2,500, Zane says, the program has paid for itself.

- COMMUNITY-SERVICE MARKETING II. Zane also never misses an opportunity to work with school-age kids. He's spoken to kindergarten classes about bike safety, helped the police register bikes, and, when Connecticut passed a bike-helmet law in 1992, persuaded Trek to help him offer $40 helmets to kids at cost ($20). "Indirectly, we profited because we did something for the community," says Zane. "We also got a lot of publicity, and that boosted sales." The cost of the helmet program: $0.

- PLAYING AS IF YOU'RE BIGGER THAN YOU ARE.

Five years ago Zane made a strategic decision to commit 25% of his then-$36,000 advertising budget to a glossy 32-page catalog filled with his merchandise, which also offered 24 generic biking tips. Though the catalog looks original, it's actually produced by a co-op company; 16 pages are customized for Zane's Cycles, while the rest might be exactly the same for another bike dealer. Zane has exclusivity with the company for New Haven and nearby Fairfield and Litchfield Counties, so there's little chance of customers' receiving a copycat in the mail. Zane says the cost--$9,000 a year--is justified by the long shelf life the catalog earns by including the tips (advice about things like how to track your heart rate or improve your off-road riding). "People will come in with things circled in the catalog several weeks after it comes out," he says. The catalog reinforces Zane's customer-service philosophy and also gives the impression that his business is much bigger than it really is. The same goes for his 800 number (800-551-BIKE), which works nationwide but is used mostly in Connecticut, where a town 5 to 10 miles away might be a toll call. "It costs me a $24 yearly fee, plus a maximum of $200 a month for incoming calls in the summer. It's an inexpensive way to make the business look big," says Zane.

Five years ago Zane made a strategic decision to commit 25% of his then-$36,000 advertising budget to a glossy 32-page catalog filled with his merchandise, which also offered 24 generic biking tips. Though the catalog looks original, it's actually produced by a co-op company; 16 pages are customized for Zane's Cycles, while the rest might be exactly the same for another bike dealer. Zane has exclusivity with the company for New Haven and nearby Fairfield and Litchfield Counties, so there's little chance of customers' receiving a copycat in the mail. Zane says the cost--$9,000 a year--is justified by the long shelf life the catalog earns by including the tips (advice about things like how to track your heart rate or improve your off-road riding). "People will come in with things circled in the catalog several weeks after it comes out," he says. The catalog reinforces Zane's customer-service philosophy and also gives the impression that his business is much bigger than it really is. The same goes for his 800 number (800-551-BIKE), which works nationwide but is used mostly in Connecticut, where a town 5 to 10 miles away might be a toll call. "It costs me a $24 yearly fee, plus a maximum of $200 a month for incoming calls in the summer. It's an inexpensive way to make the business look big," says Zane.

- FREE CELLULAR PHONES. In February 1993 Zane was talking to a customer who was in the cellular- phone business and learned that while distributors charged approximately $225 for a telephone, the phone company would actually pay a $250 commission for each activation. Zane called Bell Atlantic immediately, proposing that Zane's Cycles become a phone distributor. His plan was to give away a phone to anyone who bought a bike--a value added for customers that would actually earn him a net profit of $25. Bell Atlantic was less than enthusiastic, but the rep agreed to visit Zane's shop. "I showed her the catalog, and that really set us apart from other bike shops for her," says Zane. "She began to see us an alternative channel of distribution." Bell Atlantic signed Zane up--making him the first retailer in the area to offer free phones. He activated 500 phones the first year, which earned him $12,500, plus another $25 a phone in co-op-advertising allowances. His profits are larger now, since the cost of phones fell to about $165, but commissions have remained the same.

- COFFEE BAR AND TOY CORNER.

Two years ago Zane decided he was hitting the wall in his 900-square- foot store, so he decided to move. Planning for $500 per square foot in annual revenues and striving to build Zane's Cycles to a $2-million business over the next three years, he settled on a 4,000-square-foot space just outside the main business district. Making a personal loan of $100,000 to his business, he renovated his new store meticulously, installing the most up-to-date display racks and even including a play area for children. There was just one problem. Six months after opening the new store, he began to hear from customers that the new place wasn't intimate enough. The high ceilings and white walls were uninviting, making the store feel more like a chain than the homegrown business it was.

Two years ago Zane decided he was hitting the wall in his 900-square- foot store, so he decided to move. Planning for $500 per square foot in annual revenues and striving to build Zane's Cycles to a $2-million business over the next three years, he settled on a 4,000-square-foot space just outside the main business district. Making a personal loan of $100,000 to his business, he renovated his new store meticulously, installing the most up-to-date display racks and even including a play area for children. There was just one problem. Six months after opening the new store, he began to hear from customers that the new place wasn't intimate enough. The high ceilings and white walls were uninviting, making the store feel more like a chain than the homegrown business it was.

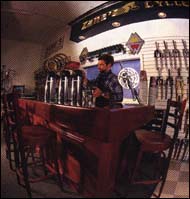

Zane thought back to a trip he had taken to Lucerne, Switzerland, where he visited a bicycle shop that had a coffee bar. "I knew what I had to do," he recalls. He commissioned a cabinetmaker to build him a 14-foot mahogany coffee bar, positioning it in front of the window that separates the repair room from the retail operation. Customers could relax over a cup of gourmet coffee (the coffee suppliers provided the equipment), mull over a purchase, or just watch the mechanics. Zane would also give kids a free Snapple and sit them in front of the Lego table or a video while Mom and Dad sipped and shopped. "People fell in love with it," he says. The bar, built for him by one of his former managers, cost about $3,000.

- FORMER COMPETITORS AS A MARKETING CHANNEL. Call two of Zane's former competitors--now put of business--and you'll get this message: "The number you are calling is no longer in service. If you are in need of a bicycle dealer, Zane's Cycles will be happy to serve you. To be directly connected toll-free, please press zero now." By offering to pay the local yellow pages a small fraction of the defunct dealers' remaining advertising costs, Zane arranged to have their out-of-service phone numbers ring at his shop. The total cost to him is about $200 a month, which he'll continue to pay until a new book is published. Because the yellow pages helped him track the transferred calls, Zane knows he received 260 inquiries from his former competitors' customers last July alone. "The first day the line was changed, we sold a bike to a guy who asked why we closed our New Haven store," recalls Zane. "So the program paid for itself for that month." It also reinforces Zane's stronger-than-the- competitors image.

- PRICE GUARANTEE. While Zane's lifetime service guarantee was one of his best selling tools, it sometimes made customers suspicious. "They'd say, 'Sure, you're giving me lifetime free service, but what are you charging me for the bike?’ " recalls Zane. He knew his prices were competitive, but customers wanted to find that out for themselves. So two years ago he started a 90-day-price-guarantee program: find it in Connecticut for less, and he'll give you the difference plus 10%. "Now we can say, 'Buy the bike, ride it, and if you find it for less, we'll take care of it.' Our pricing gained credibility." Last year, says Zane, his sales were up 54%, compared with his normal 25% growth rate; he reckons the store now handles 20% more customers. And the sales are easier. "We make money through volume because we spend less time with each customer making the hard sell--we can focus on the product," he says. Cumulatively, he's had to rebate less than $1,000. But, he says, "half the people who receive a rebate will spend it in the store that day."

"Chris's main objective is to take market share from everyone around him," says Trek's Seeger. "I've watched his numbers go straight up while sales at the New Haven shop I used to deal with have gone down. I could see that people were going to Chris." Ray Keener, executive director of the Bicycle Industry Organization, in Boulder, Colo., says that though many bike shops are run by biking enthusiasts who do a good job of appealing to passionate cyclists, "Chris is good at going out there and grabbing people who are marginally interested and getting them into the store." Once they're there, Zane makes it difficult for them to leave without buying. And once they've bought, he blitzes them with reasons to come back--a gift certificate, a reminder that a child might be ready for a larger bike, and so on.

But there is also a downside to his devotion to customer service. His service guarantee, for example, has limited his opportunity for growth. Shortly after he initiated the guarantee, he was forced to drop a line of bicycles because the warranties "were killing us." While the manufacturer covered the cost of parts, Zane was obliged to provide free labor, and the number of repairs was cutting into his already-thin margins. With a lifetime of free service on every bike sold looming ahead of him, he decided to cut his losses and drop the brand.

A foray into the world of exercise equipment has also been problematic. In the winter of 1994, Zane began carrying a high-end line of treadmills--an attempt to diversify his business and to generate more sales in the slow winter months. He learned quickly that it wasn't a good fit. "It was very different from the bike business," he says. Treadmills need adjustment more often than bikes do--and they're too big for the customer to load up and bring into the shop. We were going out to do in-home servicing every six weeks, and it cut deeply into our profits." Again he quickly cut his losses and discontinued the line. Still, he's committed to servicing the machines he's already sold--for life. An expensive mistake? Zane shrugs. "Those customers will see that we're honoring our commitment to them even though we're not carrying the line anymore, and they'll speak well of us."

It's a phrase Zane uses a lot when he's referring to customers--"they'll speak well of us." Indeed, every marketing gimmick, every guarantee, every freebie is designed in light of Zane's belief that the most sophisticated marketing in the world won't serve him as well as customer referrals. And that all comes down to how people are treated in the store. Zane doesn't, for example, make a point of hiring cyclists as salespeople. "I can teach anyone about a bike," he says, "but I can't teach them to be helpful or courteous. I've had people who know the product cold but who just don't have the ability to work with customers. They don't last long."

The attention to detail is an integral part of Zane's basic business philosophy, but it's also critical to his survival. Wal-Mart is coming to town, as is Ski Market, a category-killer sporting-goods store. "When a category killer comes in, you have to have all your programs in place," says Zane. "You have to work to be as strong as they are and kill them where they're weak. And customer service is where they're weakest."

He is not, in fact, comfortable with merely serving his niche, as a good specialty retailer probably ought to be. He wants to lure customers from Wal-Mart and reckons that the giant's presence will actually help him because "there will be more inexpensive bikes out there that need to be fixed." Soon he'll have a better point-of-sale computer system that will help him track customers more effectively and do more targeted marketing. Down the line, once he's hit his 1997 goal of $2 million in sales, he'll cautiously explore other markets.

And how do his competitors fit into all this? Well, they don't. "Our 100% goal is to be the bike shop in New Haven County," says Zane. "And we won't stop there."

One project, however, he did stop pursuing. For seven years he had juggled college and the demands of company building, completing three years of course work toward the degree he had promised his parents he'd earn. It was a struggle. Finally, Patricia and John Zane relented. They were satisfied their son was on the road to success and were convinced of his commitment to the community. Chris, relieved to be let off the hook but uncomfortable with the prospect of unfinished business, presented an alternative scenario. "I want to be so successful that I'll be asked to give a commencement speech, and that's how I'll earn my degree," he told them. "It's not the traditional way, but there's no right path," he philosophized. He was, in fact, living proof of that. So in 1990, his parents transferred to him 80% of the stock. He'd earned it.